🏠 Residential Design Standards

Interactive Visualization of IRC Requirements and Housing Analysis

IRC Minimum Requirements

| Space Type | Min Area (sq ft) | Min Dimension (ft) | Ceiling Height (ft) | Glazing (%) | Ventilation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living Room | 70 | 7 | 7.0 | 8 | 4 |

| Bedroom | 70 | 7 | 7.0 | 8 | 4 |

| Kitchen | No minimum | — | 7.0 | 8 | 4 |

| Bathroom | Not habitable | — | 6.67 | Not required | Mechanical OK |

| Hallway | Not habitable | — | 7.0 | Not required | Not required |

Ceiling Height Comparison (inches)

🔑 Key IRC Sections

- Section R303: Light, ventilation, and heating requirements for all habitable spaces

- Section R304: Minimum room areas (70 sq ft with 7 ft minimum dimension)

- Section R305: Ceiling heights (7 ft habitable rooms, 6’8″ bathrooms, special rules for sloped ceilings)

Housing Types Comparison

Detailed Comparison Table

| Housing Type | Average Size | Land Use Index | Cost Index | Shared Spaces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Single-Family | 2,200 sq ft | 100% (baseline) | 100% (baseline) | 0% |

| ADU (Accessory Dwelling) | 900 sq ft | 30% | 45% | 20% |

| Tiny House | 350 sq ft | 15% | 25% | 0% |

| Cohousing Unit | 1,200 sq ft | 40% | 60% | 85% |

💡 Key Insights

- ADUs provide 60% space reduction while using only 30% of typical land footprint

- Tiny Houses are legally defined as 400 sq ft or less (IRC 2021, Appendix AQ)

- Cohousing balances smaller private units with extensive shared amenities (85% shared space index)

- Traditional homes offer maximum privacy but highest per-capita resource consumption

- Zoning changes in many cities now permit 2-3 units per formerly single-family lot

Glazing & Ventilation Requirements

IRC Section R303: All habitable rooms require minimum 8% glazing (windows) and 4% operable ventilation

📐 Example Calculation

For a 200 square foot bedroom:

- Minimum total window area: 200 × 0.08 = 16 sq ft

- Minimum operable area: 200 × 0.04 = 8 sq ft

- Practical solution: Two 3′ × 4′ windows = 24 sq ft total (exceeds minimum), with 12 sq ft operable

- Alternative: Use mechanical ventilation system to meet the 4% ventilation requirement

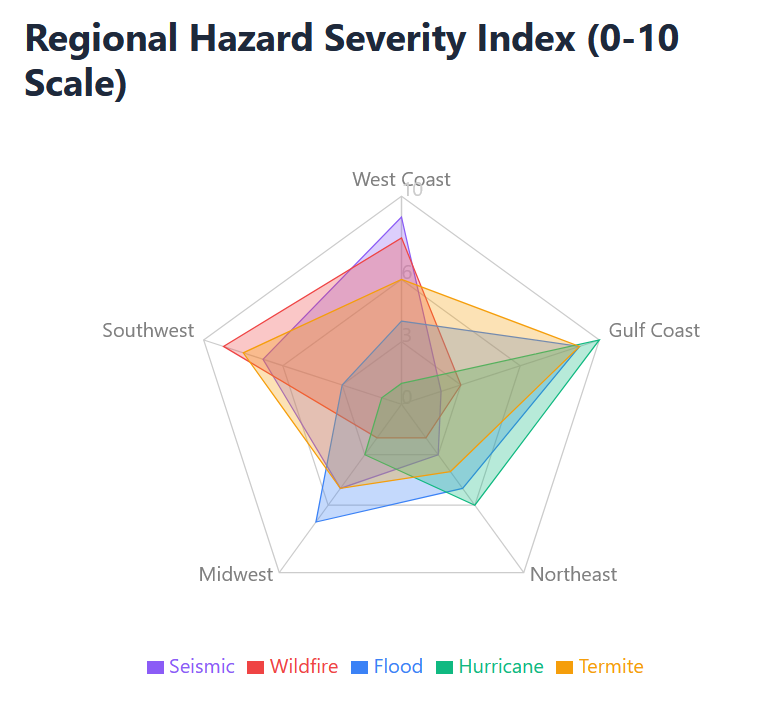

Regional Environmental Hazards

Primary Code Requirements by Hazard Type

🔥 Wildfire (WUI)

- • IWUIC compliance required

- • Fire-resistant roofing materials

- • Defensible space landscaping

- • Ember-resistant vents

- • NFPA 1144 standards

- • California Chapter 7A

💧 Flood Zones

- • Base Flood Elevation (BFE)

- • Elevated foundations/pilings

- • Flood-resistant materials

- • FEMA compliance

- • Proper drainage systems

- • Flood vents required

⚡ Seismic Activity

- • Seismic Design Categories

- • Foundation anchor bolts

- • Structural reinforcement

- • Shear wall requirements

- • Hold-down connections

- • Flexible utility lines

🌪️ Hurricane Zones

- • Wind speed design ratings

- • Impact-resistant glazing

- • Roof-to-wall connections

- • Storm shutters/protection

- • Enhanced tie-downs

- • Hurricane straps

📊 Wildfire Statistics

Since the 1990s, average annual wildfire acreage in the United States has more than doubled. Development in Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) areas—where structures meet burnable vegetation—continues to accelerate dramatically, making fire codes increasingly critical for new residential construction in these high-risk zones.

Fire Safety System Requirements

Smoke Alarm Requirements (IRC Section R314)

✓ Required Locations

- • Inside each sleeping room

- • Immediately outside each sleeping area

- • On every story of the dwelling

- • In all open hallways

- • Interconnected (all alarms sound together)

✗ Placement Restrictions

- • Minimum 3 feet from bathroom doors

- • (applies to bathrooms with tub/shower)

- • Avoid dead air spaces near corners

- • Follow manufacturer specifications

- • Not near cooking appliances

Carbon Monoxide Alarm Requirements (IRC Section R315)

⚠️ Required When:

- ✓ Fuel-fired appliances present (gas furnace, water heater, dryer)

- ✓ Attached garage with access to dwelling

- ✓ Fireplace or wood-burning stove installed

- ✓ Any combustion equipment in home

✓ Not Required When:

- ✓ All-electric home (no combustion sources)

- ✓ No attached or tuck-under garage

- ✓ No solid-fuel burning appliances

- ✓ No gas lines to property

🔥 The Residential Sprinkler Paradox

Despite IRC Section R313 requiring automatic fire sprinkler systems in all new one- and two-family dwellings and townhouses, only 2 states currently mandate statewide compliance:

Most jurisdictions have opted out of mandatory sprinkler requirements due to construction cost concerns, despite proven life-safety benefits and insurance premium reductions. This creates a significant gap between model code recommendations and actual enforcement nationwide.

Designing Living Spaces: A Framework for Functional Residential Architecture

Understanding Human-Centered Design

When we design spaces where people live, work, and rest, we’re not simply arranging walls and furniture—we’re creating environments that must accommodate the complex reality of human bodies in motion. The science of measuring human dimensions, anthropometrics, gives us the raw data: how tall we stand, how far we reach, how much space we occupy. But transforming these measurements into livable spaces requires ergonomics, the art and science of applying human factors to practical design solutions.

It’s crucial to recognize that the measurements and standards discussed here reflect North American norms. Human spatial preferences aren’t universal—they shift dramatically across cultures. A dining arrangement that feels comfortable in Toronto might seem oddly spacious or cramped in Tokyo. This cultural relativity extends beyond mere preference into the realm of proxemics, where invisible boundaries of personal space vary significantly depending on cultural context.

The Architecture of Movement: Spatial Flow and Function

Every successful residential space tells a story of movement and purpose. Consider how you navigate your own home: the path from bedroom to bathroom in the morning, the dance between refrigerator, sink, and stove while preparing meals, the way you move through a hallway while carrying laundry. These patterns of movement define what we call organizational flow—the orchestration of activity zones, circulation paths, and functional areas within a room.

Take bedrooms as an example. While sleep is the primary function, a well-designed bedroom must also accommodate:

- Accessing clothing storage without disturbing a sleeping partner

- Moving between the bed and adjacent bathroom

- Creating workspace for reading, computing, or personal tasks

- Maintaining clear pathways that don’t require navigation around furniture corners in darkness

Each room in a residence operates as its own ecosystem of activities, and successful design requires understanding not just what happens in that space, but how those activities sequence and overlap throughout daily life.

The Regulatory Landscape: Codes as Design Parameters

Defining Our Terms

Before diving into regulations, we need clarity on terminology. Codes are comprehensive rule systems developed by experts and grounded in research. They represent recommended best practices that jurisdictions can adopt wholesale or modify for local conditions. Once adopted, they become legally enforceable. Standards, by contrast, provide the technical backbone—testing procedures, material specifications, and measurement protocols that define how to meet code requirements.

Think of it this way: a code tells you that a stairway must be safe; a standard tells you exactly how to measure riser height and tread depth to achieve that safety.

The Code Ecosystem

The International Code Council (ICC), formed in 2000, represents a watershed moment in American building regulation. Their International Building Code (IBC) serves commercial and public structures, while the International Residential Code (IRC) specifically governs single-family and two-family dwellings. This distinction is critical: the IRC doesn’t extend to apartments, dormitories, nursing facilities, or other multi-family housing—those fall under IBC jurisdiction.

However, adopting “international” codes doesn’t mean uniformity. States and municipalities regularly modify these model codes to address regional challenges—hurricane winds in Florida, seismic activity in California, winter conditions in Minnesota. Before beginning any project, designers must investigate the specific regulations governing their location.

Zoning: The First Layer of Constraint

While building codes govern how you build, zoning regulations control what and where you can build. These local ordinances dictate:

- Maximum building height and total square footage

- Setback distances from property lines

- Permitted land uses

- Parking requirements

- Lot coverage percentages

Zoning regulations vary wildly—from highly restrictive urban areas with extensive design review boards to rural jurisdictions with minimal oversight.

Emerging Housing Paradigms

Contemporary housing faces a perfect storm of challenges: skyrocketing land costs, shrinking affordability, social isolation, and environmental consciousness. These pressures are generating innovative housing models that challenge traditional zoning frameworks.

Accessory Dwelling Units: Reimagining the Single-Family Lot

ADUs—known colloquially as granny flats, in-law suites, or carriage houses—represent secondary dwellings on lots traditionally reserved for single homes. A converted garage, a basement apartment, or a purpose-built tiny home on the main house’s lot all qualify as ADUs.

Progressive municipalities are rewriting zoning codes to permit ADUs, often with specific requirements regarding:

- Maximum square footage (commonly 800-1,200 square feet)

- Owner occupancy of either the primary or accessory unit

- Off-street parking provision

- Architectural compatibility with the main dwelling

- Utility connection standards

This regulatory evolution recognizes ADUs as a practical response to housing shortages without dramatically altering neighborhood character.

Tiny Houses: Minimalism Meets Regulation

The tiny house movement celebrates dwellings of 400 square feet or less (excluding loft spaces). The 2021 IRC now includes Appendix AQ specifically addressing tiny houses, marking their transition from fringe experiment to recognized housing type.

The regulatory picture splits along a critical divide:

- Foundation-based tiny houses can qualify as primary dwellings or ADUs, subject to standard residential codes

- Wheeled tiny houses fall under RV regulations, and many jurisdictions prohibit permanent RV habitation on residential lots

This creates a paradox: the mobility that makes tiny houses affordable and flexible also renders them legally problematic in many communities.

Cohousing: Private Life with Shared Infrastructure

Originating in 1970s Denmark, cohousing blends private residences with substantial shared amenities—communal kitchens, dining halls, workshops, gardens, and recreational spaces. Residents maintain individual homes (typically smaller than conventional single-family houses) but share resources and community spaces.

The model offers compelling advantages: reduced per-household costs, environmental efficiency through shared resources, built-in social networks, and communal support systems. From a regulatory perspective, cohousing developments may be structured as condominiums, cooperatives, or planned communities, each with distinct legal implications.

Critical Code Requirements for Habitable Spaces

The IRC establishes specific parameters for spaces designated as “habitable”—rooms used for living, sleeping, eating, or cooking. Notably excluded from this definition: bathrooms, closets, hallways, storage areas, and utility rooms.

Natural Light and Ventilation (Section R303)

Every habitable room requires:

- Glazing (windows) totaling at least 8% of floor area

- Operable openings for ventilation equal to at least 4% of floor area (with exceptions for mechanical ventilation systems)

For a 200-square-foot bedroom, this translates to roughly 16 square feet of window area, with at least 8 square feet capable of opening for fresh air.

Room Dimensions (Section R304)

With the exception of kitchens, every habitable room must provide:

- Minimum 70 square feet of floor area

- No dimension less than 7 feet

This prevents the creation of narrow, tunnel-like spaces that feel oppressive regardless of total square footage.

Ceiling Heights (Section R305)

Standard habitable spaces require 7-foot minimum ceiling height, with specific exceptions:

- Bathrooms, toilet rooms, and laundries: 6 feet, 8 inches

- Basement beams and girders: 6 feet, 4 inches (with spacing considerations)

- Sloped ceilings: At least 50% of required floor area must maintain 7-foot height, with remaining areas no lower than 5 feet

This last provision enables attic conversions and rooms with cathedral ceilings to qualify as habitable despite varying heights.

Life Safety Systems

Modern residential code increasingly emphasizes active fire protection:

Sprinkler Systems (Section R313): Required in new townhouses and single/two-family dwellings, though as of this writing, only California and Maryland mandate residential sprinklers statewide.

Smoke Alarms (Section R314): Required in sleeping rooms, immediately outside sleeping areas, on each story, and in open hallways—positioned at least 3 feet from bathroom doors containing showers or tubs.

Carbon Monoxide Alarms (Section R315): Mandatory in dwellings with fuel-fired appliances or attached garages communicating with living spaces.

Environmental Hazards and Regional Adaptations

Wildland-Urban Interface: Building in Fire Country

As development pushes into wildland-urban interface (WUI) zones where structures meet burnable vegetation, fire-related codes gain critical importance. Since the 1990s, average wildfire acreage in the U.S. has more than doubled, driving regulatory response.

Three primary codes govern high-fire-hazard construction:

- ICC Wildland-Urban Interface Code (IWUIC)

- NFPA 1144 (Standard for Reducing Structure Ignition Hazards)

- California Building Code Chapter 7A (Materials and Construction Methods for Exterior Wildfire Exposure)

These regulations address exterior materials (roofing, siding, decking), vegetation management (“defensible space”), and vulnerable building elements like vents, eaves, and rain gutters that can catch embers.

Other Regional Hazards

The IRC includes provisions for geography-specific risks:

- Seismic zones: Structural reinforcement and foundation requirements

- Hurricane regions: Wind-resistant construction and impact-rated glazing

- Flood zones: Base Flood Elevation (BFE) requirements mandating elevated construction

- Termite zones: Soil treatment and barrier requirements

FEMA flood maps establish BFE—the water level elevation with a 1% annual probability of occurrence—which determines whether homes must be elevated on pilings or other flood-resistant construction techniques.

Code as Creative Framework

While regulations might seem constraining, they actually establish a foundation for creativity within safe, functional parameters. Understanding codes early in the design process transforms them from obstacles into productive constraints that guide toward better solutions. The most successful residential designs don’t fight regulations—they leverage them as part of a holistic approach to creating spaces that serve human needs while meeting safety, health, and environmental standards.