🏠 The Hidden Language of Home

How Spaces Shape Our Lives: An Interactive Journey

The Invisible Architecture of Home

Walk into any house, and you’ll immediately sense something beyond walls and furniture. There’s an invisible architecture at work—a complex interplay of boundaries, territories, and unspoken rules that define how we live, interact, and feel safe within our homes.

Four Zones of Territory

Oscar Newman’s groundbreaking research revealed that our homes exist within four distinct territorial zones, each serving a unique psychological and social function.

Streets, sidewalks, shared spaces

Front yards, planted strips

Porches, shared courtyards

Interior spaces, fenced yards

| Territory Type | Examples | Characteristics | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Streets, sidewalks, parks | Open to everyone, no individual control | Community interaction, movement |

| Semi-Public | Planted parkways, community gardens | Publicly owned, privately maintained | Transition zone, community pride |

| Semi-Private | Front porches, shared yards | Limited access, visual openness | Social interaction, surveillance |

| Private | Home interior, fenced backyards | Full control, restricted access | Security, personal expression |

The Intimacy Gradient

Christopher Alexander discovered that the best homes create a gradual transition from public to private spaces. Hover over each section to see how space flows:

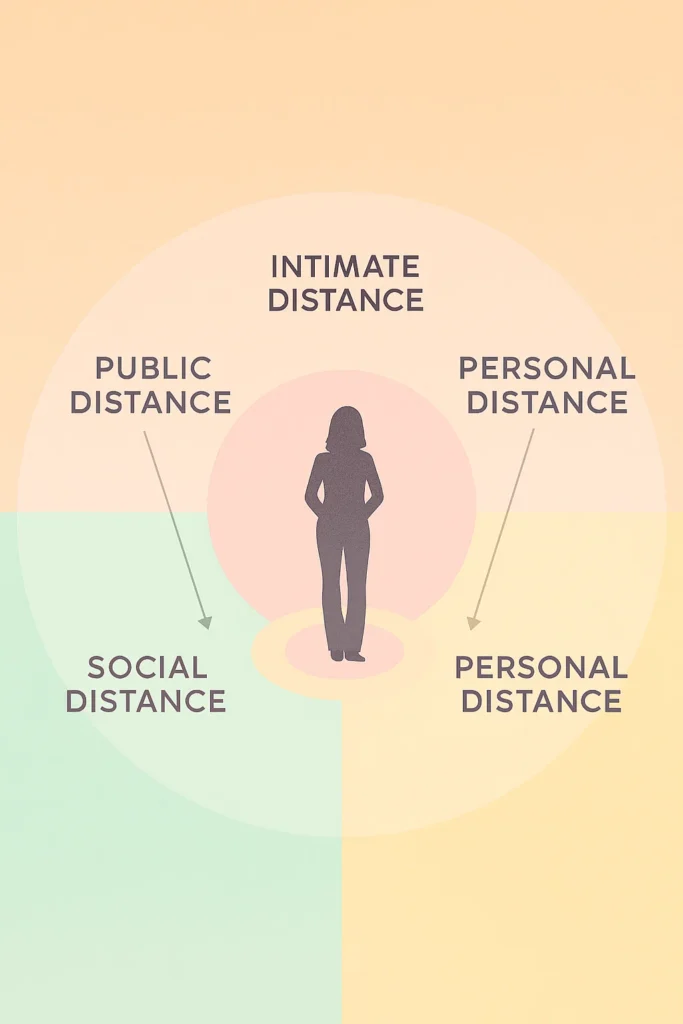

Edward Hall’s Four Distance Zones

Anthropologist Edward Hall identified four distinct spatial boundaries that govern human interaction. These invisible zones are crucial for designing comfortable living spaces.

| Distance Type | Range | Appropriate For | Design Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intimate | 0-18 inches (0-0.5 m) | Close family, romantic partners | Private bedrooms, personal reading nooks |

| Personal-Casual | 1.5-4 feet (0.5-1.2 m) | Friends, family conversations | Living room seating, dining arrangements |

| Social-Consultative | 4-12 feet (1.2-3.7 m) | Business, acquaintances | Home offices, formal dining, entryways |

| Public | 12+ feet (3.7+ m) | Formal gatherings, strangers | Large gathering spaces, yards |

How Families Map Their Territories

Sebba and Churchman’s research in Israeli high-rise apartments revealed three distinct territorial layers within homes:

🏠 Public/Family Areas

- Living rooms

- Dining spaces

- Kitchen (often)

- Shared hallways

Function: Spaces where the entire family gathers and interacts

👥 Shared/Sub-Group Areas

- Parents’ bedroom

- Siblings’ shared room

- Guest bedroom

Function: Spaces belonging to smaller groups within the family

👤 Individual Areas

- Private bedrooms

- Personal desks

- Individual chairs

- Personal shelves

Function: Personal territories reflecting individual identity

🪑 Micro-Territories

- “Dad’s chair”

- One side of shared room

- Specific kitchen drawer

- Bathroom shelf

Function: Small but significant personal spaces within shared areas

Culture: The Invisible Architect

What feels like a “normal house” varies dramatically across cultures, regions, and social groups. These differences reflect deep cultural values and traditions.

Regional Differences

Climate, local materials, and geographical context shape vernacular architecture

Family Structures

Nuclear vs. extended families require different spatial arrangements

Social Customs

Cultural practices around hospitality, privacy, and daily rituals

Economic Factors

Class differences influence space expectations and priorities

Universal Design: Spaces for Everyone

Universal design creates environments usable by the widest possible range of people, regardless of age or ability. The benefits extend far beyond accessibility compliance.

Wide Doorways

32-36 inches clear passage helps wheelchair users, movers, parents with strollers

Zero-Step Entries

No stairs at entrances benefits everyone from wheelchair users to delivery people

Lever Handles

Easy to operate for people with arthritis, children, or anyone carrying items

Adjustable Features

Counters and fixtures that adapt to different heights and needs

Curbless Showers

Safe for everyone, easier to clean, modern aesthetic

Good Lighting

Benefits people with vision impairments and creates better ambiance for all

| Concept | Focus | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Accessible Design | Specific disability accommodation | Ensures people with disabilities can use spaces independently |

| Universal Design | Usability for everyone | Benefits all users regardless of age or ability |

| Adaptable Design | Flexibility over time | Spaces easily modified as needs change |

| Visitability | Basic home access | Ensures homes can be visited by people with mobility limitations |

The Three Pillars of Sustainable Housing

True sustainability emerges where social, economic, and environmental concerns intersect. Each pillar is essential and interdependent.

Viability

Efficiency

Affordability

Conservation

Protection

Stewardship

SUSTAINABILITY

| Pillar | Key Questions | Design Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Social | Does housing support wellbeing, equity, and community? Is it healthy and affordable? | Indoor air quality, natural light, community spaces, accessibility |

| Economic | Can people afford to build, maintain, and operate their homes long-term? | Energy efficiency, durable materials, local sourcing, lifecycle costs |

| Environmental | What is the impact on natural systems, now and for future generations? | Energy consumption, material sourcing, water conservation, site impact |

Understanding Key Terms

| Term | Definition | Emphasis |

|---|---|---|

| House | The physical structure with walls, roof, and architectural features | Material and measurable aspects |

| Home | The emotional and psychological relationship with a place | Attachment, meaning, identity |

| Dwelling | Both the place and the activity of living; to make one’s abode | Process and artifact combined |

| Residence | Legal term describing place of domicile | Legal and administrative purposes |

Walk into any house, and you’ll immediately sense something beyond walls and furniture. There’s an invisible architecture at work—a complex interplay of boundaries, territories, and unspoken rules that define how we live, interact, and feel safe within our homes.

The Invisible Boundaries We Create

In the 1970s, researcher Clare Cooper made a curious observation. She noticed that homes seemed to exist in two distinct worlds: what she called the “intimate interior” and the “public exterior.” It was a simple idea, yet it captured something profound about how we experience our living spaces—the way certain areas feel deeply personal while others remain open to the outside world.

Around the same time, architect Oscar Newman was studying something troubling: why some neighborhoods felt safe while others didn’t. His research led him to coin the term “defensible space,” revealing that our sense of security isn’t just about locks and alarms. It’s about how spaces are designed to give residents a sense of control.

Newman identified four distinct zones radiating outward from our private sanctuaries. Public territories like streets and sidewalks belong to everyone and no one. Then come semipublic spaces—those planted strips between sidewalk and street that homeowners tend but don’t technically own. Moving inward, semiprivate territories include front yards, shared courtyards, and porches—threshold spaces that aren’t quite public, not quite private. Finally, there’s private territory: the fenced backyard, the locked apartment, the bedroom with a closed door.

What Newman discovered was striking: homes need breathing room between these zones. Without some kind of buffer between the public world and private interior, residents never quite feel in control. They remain perpetually exposed, always on guard.

How Families Map Their Territories

Inside apartments in Tel Aviv, researchers Rachel Sebba and Arza Churchman were documenting something fascinating. They watched how families carved up their living spaces into invisible territories, creating a micro-geography of belonging within four walls.

They found three distinct layers. Public areas—living rooms, dining spaces—belonged to everyone in the family. Shared areas like parents’ bedrooms or siblings’ rooms belonged to smaller groups. But even within these shared spaces, individuals staked claims to particular territories.

Picture a shared bedroom: two beds separated by an imaginary line down the middle. Or a living room where everyone knows that’s Dad’s chair, even though no one has ever put up a sign. These weren’t random arrangements. They were families negotiating complex relationships through spatial organization, creating order and personal identity within communal living.

The research revealed something important: even in tight quarters, people need spaces they can call their own. A chair. A side of the room. A shelf. These small territories become anchors of identity and autonomy.

The Journey from Public to Private

Architect Christopher Alexander observed that the best homes don’t just separate public from private—they create a gradual transition. He called this the “intimacy gradient.”

Imagine entering a thoughtfully designed home. You step onto a porch or into a small foyer—a threshold space that’s neither fully outside nor inside. Moving forward, you enter a living room where guests are welcome. Beyond that might be a dining area or family room, slightly more personal. Further still are bedrooms and bathrooms, the most private sanctuaries.

This sequential arrangement isn’t arbitrary. It respects our psychological need for both connection and solitude. Guests never accidentally wander into private zones, and family members can retreat progressively deeper into the house when they need genuine privacy.

The Space We Carry With Us

In the 1960s, psychologist Robert Sommer was studying something peculiar: the invisible bubble of space everyone carries around their body. He called it “personal space”—an area with an invisible boundary that moves with us wherever we go. When someone invades this space uninvited, we feel uncomfortable, even threatened, though we might struggle to explain why.

Meanwhile, anthropologist Edward Hall was measuring something different. He noticed that across cultures, people maintain predictable distances based on their relationships and situations. He called his study “proxemics” and identified four zones that govern human interaction.

The intimate zone—from touch to about 18 inches—is reserved for the closest relationships. Try having a stranger stand this close to you, and you’ll immediately feel the discomfort. The personal zone, from about 1.5 to 4 feet, is where most casual conversation with friends and family happens. Stand too far from a friend during conversation, and the interaction feels cold; stand too close, and it feels invasive.

The social zone, from 4 to 12 feet, is perfect for business interactions and conversations with acquaintances. This is where most formal social interaction occurs. Beyond 12 feet lies the public zone, where interaction becomes limited and formal—the distance of lectures, presentations, or simply coexisting in public space.

These distances aren’t just theoretical. They have real implications for home design. Arrange living room seating within personal-casual distance, and conversation flows naturally. Space it too far apart, and the room feels unfriendly. Understanding these invisible boundaries helps create spaces that facilitate the right kind of interaction for their intended purpose.

When COVID-19 introduced the term “social distancing” into everyday vocabulary—roughly 6 feet apart—it placed people at the boundary between personal and social zones. Close enough for interaction, far enough for safety. This distance, it turns out, wasn’t arbitrary but aligned with Hall’s decades-old research on comfortable social interaction.

Culture: The Invisible Architect

Ask someone to describe a “normal house,” and their answer reveals more about their background than they might realize. In New Jersey, normal might mean a colonial-style home with a basement. In California, it could be a ranch house with a yard. In New Mexico, perhaps an adobe structure with thick walls and small windows designed to combat desert heat.

Researchers Delmar Jones and Joan Turner put it perfectly: “In most societies a house is more than a physical structure—it has social and cultural significance. Its very shape is often determined by cultural tradition, and it is saturated with cultural memories.”

Culture doesn’t just influence what houses look like; it shapes how people use them. In some cultures, removing shoes at the door is non-negotiable. In others, kitchens are social centers where friends and family gather while cooking. Some cultures prize individual bedrooms for children, while others see shared sleeping spaces as strengthening family bonds.

This creates a challenge for designers. When architects and designers come from different cultural backgrounds than their clients, misunderstandings can occur. Anthropologists Erve Chambers and Setha Low call this “cultural distance”—the gap between the values and perspectives of those who design housing and those who will live in it.

The consequences of ignoring cultural distance can be severe. Public housing projects designed without understanding residents’ cultural needs have sometimes become uninhabitable, not because of structural flaws but because the spaces didn’t align with how people actually wanted to live. Kitchens too small for traditional cooking methods. Living rooms arranged for nuclear families in communities where extended family gatherings are central. Lack of outdoor spaces in cultures where much of daily life happens outside.

Designer Galen Cranz emphasizes that culture isn’t just about ethnicity or nationality. Even within the same country, class differences, age differences, and gender differences affect what makes a house feel like home. A retiree’s needs differ dramatically from a young family’s. What feels spacious to one person might feel empty to another.

Learning Through Observation

This is where ethnography—the art of careful observation—becomes invaluable. Originally developed by anthropologists studying distant cultures, ethnographic methods have been adapted by designers seeking to understand the people they’re designing for.

Design ethnography involves spending time with people in their actual living environments, watching how they use spaces, asking questions, and gaining insights that surveys and interviews might miss. A designer might notice that a family never uses their formal dining room but gathers around the kitchen counter for meals. Or that teenagers treat the garage as their primary social space. Or that working parents need quiet zones for video calls.

These observations, seemingly small, can transform design decisions. They reveal the gap between how designers think people will use spaces and how they actually do. They uncover needs people themselves might not articulate. They bring cultural assumptions into the light where they can be examined and addressed.

The Wisdom of Vernacular Architecture

Long before architects and designers, people built homes using local knowledge passed down through generations. These structures—called vernacular architecture—represent centuries of trial and error, adaptation to local conditions, and cultural evolution.

In the American Southwest, thick adobe walls and small windows combat intense desert heat. In coastal regions prone to hurricanes, raised foundations and strong roofing systems protect against flooding and wind. In cold climates, compact designs with small windows minimize heat loss. In hot, humid areas, wide eaves, cross-ventilation, and raised floors combat heat and moisture.

These weren’t arbitrary design choices. They were sophisticated responses to climate, available materials, and local resources developed over generations. Before global supply chains made any building material available anywhere, vernacular builders used what was at hand: stone, timber, earth, thatch, whatever the local environment provided.

Modern architects and designers are rediscovering the wisdom in vernacular traditions. As concerns about sustainability and environmental impact grow, looking to how humans successfully adapted to diverse climates for thousands of years offers valuable lessons. Passive cooling techniques, natural ventilation, solar orientation—these strategies work with nature rather than fighting it.

Decoding the Language: House, Home, and Dwelling

The words we use to talk about where we live carry subtle but important distinctions. “House” typically refers to the physical structure—walls, roof, plumbing, electrical systems. It’s the architectural object, the thing that can be measured, photographed, and sold.

“Home” means something deeper. It’s the emotional and psychological relationship we have with a place. You can live in a house without it feeling like home. Home is where you feel safe, where you can be yourself, where memories accumulate. It’s a reflection of identity, status, and personal meaning.

Research shows that home encompasses multiple dimensions: security, togetherness with family and friends, personal status and identity, and a material structure reflecting the owner’s ideas and values. Different academic disciplines emphasize different aspects—sociologists focus on class, gender, and tenure, while psychologists emphasize attachment and personal meaning.

“Dwelling” captures both the place and the activity of living. To dwell is to inhabit, to make one’s abode in a place. It encompasses the everyday activities that constitute living: cooking, sleeping, eating, relaxing, working, playing. Dwelling is both process and artifact—the action of residing and the structure where it happens.

Understanding these distinctions helps designers think more precisely about what they’re creating. Are they designing houses—efficient, functional structures? Or are they creating frameworks for homes—spaces where emotional connections and personal meaning can flourish? Are they facilitating dwelling—supporting the full range of daily activities that make up a life?

Opening Doors: The Evolution of Accessible Design

For decades, accessibility was an afterthought in home design. If considered at all, it meant awkward ramps added to existing structures or institutional-looking grab bars that screamed “disability.” The approach was reactive, addressing problems after they occurred rather than preventing them through thoughtful design.

Then something shifted. Architects and designers began asking a different question: What if we designed homes that worked for the widest possible range of people from the start?

This thinking led to universal design—a philosophy pioneered by architect Ron Mace. Rather than creating separate “accessible” versions of things, universal design seeks to make everything usable by as many people as possible, regardless of age or ability, without special adaptation.

Consider the humble lever door handle. Unlike traditional round knobs requiring grip strength and twisting motion, lever handles can be operated with an elbow, forearm, or closed fist. They help people with arthritis, people carrying packages, parents holding babies, children, elderly people—essentially everyone. That’s universal design: solutions that benefit everyone, not just people with diagnosed disabilities.

The implications for home design are profound. Wide doorways help wheelchair users, but they also make moving furniture easier and feel more spacious. Zero-step entries help people using wheelchairs or walkers, but they also help parents with strollers, delivery people, and anyone who’s ever struggled to carry groceries up stairs. Extra floor space in bathrooms accommodates wheelchairs while making spaces feel more luxurious for everyone.

Adaptable design takes this further, creating elements that can be easily modified as needs change. Counters that adjust in height. Cabinets with removable fronts that can create knee space when needed. Showers with seats that fold away when not required. These features acknowledge that people’s abilities change over time—through aging, temporary injuries, or shifting circumstances.

The visitability movement focuses specifically on ensuring homes can be visited by people with physical disabilities. The criteria are straightforward: at least one zero-step entrance, wide doors on the main floor, and a bathroom on the main floor. These simple features mean that grandparents using wheelchairs can visit their grandchildren, friends recovering from surgery aren’t excluded from gatherings, and neighbors with mobility limitations can maintain social connections.

While most single-family homes aren’t legally required to be accessible, many homeowners now seek these features proactively. Some are planning to “age in place”—to remain in their homes as they grow older rather than relocating to assisted living. Others have family members with current accessibility needs. Either way, the demand for universally designed homes continues to grow.

Federal regulations do affect multifamily housing. The Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 requires new buildings with four or more units to provide basic accessibility to first-floor units and all units in buildings with elevators. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act affects federally funded housing. The Americans with Disabilities Act, while focused on public buildings, has increased the availability of accessible products and fixtures that benefit residential design.

Building for Tomorrow: Sustainability in Housing

The concept of sustainability entered mainstream consciousness with the 1987 Brundtland Report, which offered a deceptively simple definition: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

It sounds straightforward until you start unpacking its implications. Meeting current needs without compromising the future requires rethinking nearly everything about how we build, operate, and live in homes.

The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals, adopted in 2015, recognize that sustainability isn’t just about environmental protection. It’s an interconnected system with three dimensions: social, economic, and environmental. These aren’t separate concerns but interwoven challenges that must be addressed together.

Social sustainability asks whether housing supports human well-being, equity, and community. Does it promote health? Does it strengthen social connections? Is it affordable across income levels?

Economic sustainability examines long-term viability. Can people afford to maintain and operate their homes? Do building methods create local jobs? Are resources used efficiently?

Environmental sustainability addresses impact on natural systems. How much energy does the home consume? What materials were used, and where did they come from? How will the building affect its site over decades?

These three pillars overlap and depend on each other. A home might be environmentally efficient but economically inaccessible. It might be affordable but built with materials that harm workers’ health. True sustainability emerges where all three concerns align—where homes are environmentally responsible, economically viable, and socially beneficial.

For designers, this means expanding the scope of consideration beyond aesthetics and function to encompass lifecycle impacts, material sourcing, energy performance, water conservation, indoor air quality, site selection, and community effects. It means designing homes that aren’t just comfortable today but remain viable and healthy for generations to come.

The research and theories explored here—from territorial boundaries to cultural considerations, from accessibility to sustainability—form an interconnected web of knowledge. Each strand informs the others. Understanding personal space helps create better social sustainability. Appreciating cultural differences leads to more socially equitable design. Universal design principles often align with environmental sustainability by creating adaptable spaces that don’t require renovation as needs change.

Today’s housing challenges are complex: aging populations, climate change, housing affordability crises, increasing diversity, and evolving family structures. Addressing these challenges requires drawing on insights from psychology, anthropology, sociology, environmental science, and lived experience. It requires designers who see homes not as isolated objects but as dynamic systems embedded in cultural, social, and environmental contexts.

The most successful homes emerge when designers integrate all these considerations—creating spaces that respect territorial needs and cultural traditions, accommodate diverse abilities, support social connections, and minimize environmental impact. These homes don’t just shelter bodies; they support lives, honor identities, strengthen communities, and tread lightly on the earth. They transform houses into true dwellings where human flourishing becomes possible, now and for generations to come.