That evening I had arrived in Cumayıbâlâ from Demirhisar late and tired. The weather had been very hot during the day. My headache prevented me from even noticing the hungry bedbugs of the old and filthy hotel. But in the morning, cries and folk songs mixed with the sounds of zurna and drums woke me up. I opened my eyes. A scorching sun was overflowing through the dusty and pale red curtains, filling the entire room. As I stretched, I remembered that it was the second year of our false revolution, this poor makeshift Turkish revolution that was in reality nothing but a pitiful, bloodless flood of meaningless applause. Yes, today was the national holiday!… “But I wonder which nation’s holiday?” I thought as I got up. I approached the window. Outside, a chaotic crowd was flowing by, undulating and seething. Across the way, the rotten wooden-benched shops of Vlachs and Bulgarians were open. Their owners were looking with smiles at the gold-embroidered vested Turkish youths passing before them, like newly arrived foreign masters of this land. This “Tenth of July” parade, this demonstration was truly worth watching. I left washing my face for later, pulled up the chair. I opened the window and sat down. A little ahead, the gramophone at the Jew’s Red Cafe, as if it knew about these movements and demonstrations and wanted to join in that noise, was howling with all its might, making even more noise than before, and from afar, a band sound rumbling with hand claps and “Long live!” cries was approaching. A detachment from the Cumayıbâlâ infantry regiment was going to congratulate the government. The major—a gray-haired, dark-skinned man with an innocent face—was swaying on his white horse like a confused bride, looking ahead, and behind him, the eternal recruits coming in fours, like their commander looking ahead, were passing by repeating the piece that the band was playing:

Our army has sworn an oath The earth and heavens trembled

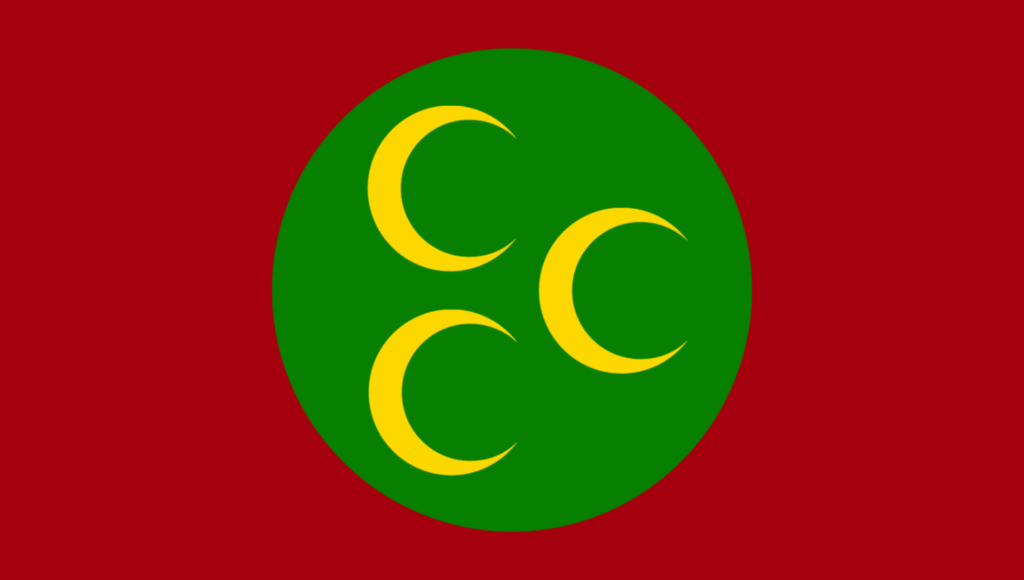

After them, a young and excessively blond gentleman dressed in gold-embroidered Turkish clothes, with a crowd of young friends, followed the soldiers puffed up as if returning from a great victory. Behind them, another crowd composed of gypsies and wretches… Then a large red flag appeared. On it were some writings with vowel marks that I could not read. Around the flag, many turbaned heads were waving like large and strange giant daisies, and behind them, khaki-clothed middle school children in pairs were shouting and seething. The refrain they kept up:

Forward, forward! Let’s take back the old places from the enemy!..

They were shouting with such heart and soul that as they passed before me, I could see the thin veins swelling in all their weak necks, red sweat flowing from under their fezzes. This flow of demonstration perhaps lasted more than half an hour. I had fallen into a trance like a dervish who had overdone the opium. I was thinking about the life of my homeland, Turkiye, this sick man believed to be surely dying, and with a bitter feeling very much resembling despair, I felt my entire mentality contracting, becoming inoperative. The door of the room opened. The Greek hotelier said my horses were ready. I was going to Razlık. So I would see tonight’s national festivities there… I got dressed immediately. While dressing, I drank the milky coffee the hotelier brought in one gulp. And I fell back into that strange and melancholy reverie!

An hour later I was climbing the steep slope up to Papazbayırı. I had dismounted from my horse. The weather was very beautiful. There wasn’t even a bit of haze in the sky. The white border towers on the ridges were shining, and whenever a light wind blew, it seemed to increase the heat of the sun. I was walking inside a flood ravine.

Large and small stones were hurting my feet and hindering the horses’ walking. There were no roads here at all. Not even a goat path… I was looking around; the places I saw did not at all resemble that famous orange-like earth we used to imagine with such importance when reading geography books as children. It was as if I was in a corner of a sphere where humans and animals did not live, for example a corner of the moon, said to be dead and frozen. Stones, stones, stones… Yellow and barren earth, scrawny and skinny trees, shrubs, bushes, again bushes… Only the telegraph poles rose like large and orphaned marks of astonishment erected at the vague traces of the civilization phantom that had once mistakenly passed through these climates, and they lined up one after another toward the forested horizons where it had fled. And travelers always went along the base of these dead poles that had turned pitch black under sun, cold, wind, blizzard and snow.

After sweating thoroughly and becoming breathless, I climbed to the top. I was going to stop to rest. A little ahead I saw a horseman. From his clothes, from the gleam of his sword, I understood he was an officer. He too had dismounted, was resting and rolling a cigarette from his pouch. I went to him. Among Turks there is no need for “introduction and formality.” I love and find this informality of ours very sincere. I approached. I greeted him. I asked where he was going. He answered with a smile:

— To Razlık, sir, and you?

— Me too.

— In that case we’ll go together.

This was a handsome, brownish, medium-height lieutenant. The large and upright head on his broad and full shoulders, the languor of his large black eyes reminded one of the pitiful quietness of captive tigers whose morals had been corrupted with whips in circuses. We began to talk. Like all Turkish officers, he attached great importance to his own knowledge and logic, to his own convictions, and was looking for an opportunity to debate. We sat on a stone there. We lit our cigarettes. About this and that… We opened the topic from politics. I said that the Tenth of July was being appreciated even in these parts. The lieutenant, as if annoyed at my surprise, said:

— Ah, what are you saying? To appreciate the Tenth of July, he said; is this even a question? This is our greatest, most glorious, most sublime day, our most sacred national holiday. I wish it were three days… Because one day and one night is very little…

— So you attach this much importance to the Tenth of July, I smiled. Since I enjoyed angering nervous debaters by saying the opposite of their claims, I added:

— And how is this a national holiday? Which nation’s holiday?

— The Ottoman nation’s…

— When you say Ottoman nation, do you mean Turks?

— No, absolutely not! All Ottomans…

In the young lieutenant’s dark black eyes, a fire of fanaticism seemed to flare. He was looking like an old-time Muslim whose religion had been blasphemed. Deciding not to start abruptly, I decided to confuse his emotional logic with rational little questions:

— Who are all the Ottomans?

— Strange question! Arabs, Albanians, Greeks, Bulgarians, Jews, Armenians, Turks… In short, all of them…

— So these are all one nation?

— Without doubt…

I laughed again:

— But I am in doubt.

— Why?

— Tell me, are Armenians not a nation?

He paused a bit. He answered with hesitation:

— Yes, they are a nation.

— Are Albanians also a nation?

— Albanians too.

— And Bulgarians?

— Bulgarians too…

— Serbs?

— Naturally, Serbs too.

Laughing and shaking my head:

— In that case you have no faith in mathematical and positive truths, I said.

He did not understand what I meant. He looked at my face. I continued:

— Let’s forget about geometry, algebra, trigonometry. In fact, you don’t even know arithmetic. You don’t know the “addition” rule of arithmetic. Or you know it but don’t believe these are correct and fundamental things.

The lieutenant’s gaze changed completely. He thought I was mocking him. Before giving him a chance to get angry, I continued again:

— Don’t misunderstand. Just answer me. Can you remember the “addition” rule in arithmetic?

— !!!

— Let me tell you. Naturally you won’t be able to deny it. Things of the same kind can be added. For example, ten chestnuts, eight chestnuts, nine chestnuts! They all make twenty-seven chestnuts, right?

— Yes!

— Things not of the same kind cannot be added. For example, ten chestnuts, eight pears, nine apples… How will you add them? This is not possible. And just as this impossibility is a mathematical and unbreakable rule, it is equally impossible to add nations whose histories, traditions, inclinations, institutions, languages and ideals are different from each other and make one nation from all of them. If you add these nations and call them “Ottoman,” you are mistaken.

The lieutenant had forgotten his cigarette. He was looking at my face as if dazed, and to turn his bewilderment at this simple and common truth that he was undoubtedly hearing for the first time into stupefaction, I was continuing my explanation more detailed and heated. I was giving many examples, explaining that the word “Ottomanism” was nothing but an official term; that the Greeks, Bulgarians, Serbs, all those nations today awakened who were once our slaves, could have no more natural, more reasonable, more logical, more rightful ideal than to take revenge on the Turks and unite with their own brothers, with the Balkan governments. But I understood very well from his eyes, from his sudden agitation, that the lieutenant did not understand.

Our cigarettes were finished. Finally:

— I cannot debate with you, he said; because our ideas are diametrically opposed…

And he stood up. I stood up too. Taking our horses by the reins, we began to walk along the edge of a sharp and rocky ridge. From the corner of my eye, without being obvious, I was looking at his face. He was very distressed, always looking at the ground. He would sometimes stop as if wanting to say something, then as if having given up, would continue walking rapidly again. Again I broke the silence:

— True, our ideas are opposed but my dear fellow, you cannot deny it; mine are correct, aren’t they?

— No, absolutely not correct, he said. From the hill we were climbing, the lowlands were now visible, the gendarme station above the Karaali Inns, the pebbly stream flowing toward Simitli was shining, in the distance small villages like piles of burnt wood were visible in the disproportionate and empty spaces of sparse and dense forests. Wiping my sweat that had started to flow again as soon as we stood up with my wet handkerchief, I insisted again:

— But why, my dear fellow, why is it not correct?..

The lieutenant was annoyed. He began with “Excuse me but…” And he burst out; if my claim were correct, wouldn’t so many great men accept it? He called all old and new government officials “great men.” Especially, if the idea of “Ottomanism” were as empty, artificial and imaginary as I said, would all political parties, both aligned and opposed, make this the basis of their programs? Were there no people left in Turkiye? Was everyone mistaken?

As he spoke, he thought himself right in his defense and logic, and the more right he thought himself, the more he burst out, and as if slightly amused, he was saying:

— So everyone in great Turkiye is ignorant and only you are learned. Everyone is mistaken and deceived and only you understand the truth, congratulations, congratulations then…

The road suddenly turned. We had to cross a deep flood ravine. We stopped. If we walked straight, the horses’ legs would be injured. Perhaps they would fall. We were not looking around. The lieutenant, delighted and laughing, cried out:

— Ah, look my dear fellow! Look, there is the witness of Ottomanism!..

With his finger he was pointing to a small Bulgarian village on the edge of a precipitous ravine about a thousand meters ahead. In this ruin standing like sweepings among a few black plowed fields, there were also a few trees. I was looking with inattentive eyes. The lieutenant, rubbing his hands as if clapping them:

— Ah, don’t you see, he said; don’t you see? Don’t you see those red freedom flags waving in that little village? Today, this sacred day when the Ottomans announce to the world that they are the most sincere and true brothers to each other… Don’t you see those red flags celebrating the Tenth of July?

I was paying attention, looking carefully and attentively. Red flags were hung on a building in the middle of the village. I couldn’t believe my eyes:

— I wonder if these are freedom flags? I said.

The lieutenant overflowed. He didn’t overflow, he practically gushed:

— You’re blind, my dear fellow, you’re plainly blind. Don’t bother to look in vain. You don’t have the capacity to see the truths. Are you still in doubt? Yes, these are freedom flags. That Ottoman-Bulgarian village lost on that mountaintop is sanctifying the Tenth of July. Do you believe it? Aren’t they Ottomans? Tomorrow when enemies attack the Ottoman homeland, they will run before you, they will shed blood in the name of Ottomanism, they will save Ottomanism with their blood…

I couldn’t contain myself:

— These Bulgarians?..

— Yes, these Bulgarians! These are the most loyal Ottomans. They have no relations with the komitadjis. They detest the komitadjis. They consider the Tenth of July the most sacred day. But you are bigoted. You won’t believe. You still say like our foolish and ignorant fathers, “No cloak from pig skin, no friend from an infidel…” and mock the ideas of humanity, brotherhood, equality born of civilization, of the great twentieth century. You cannot accept that all Ottomans are brothers. Look: A tiny village is celebrating today with red flags. Who knows, in the evening how they will have fun, how they will drink and shout “Long live Ottomanism, down with discord!” in honor of this great day…

I was silent and listening. The lieutenant was bursting out, describing the dream of Ottomanism waving with the illusions and mirages of the Tanzimat talisman, its sweet delusions, saying that no one could conquer the great Ottoman nation anymore. We were still standing at the edge of the ravine, across from the Bulgarian village where red flags were visible in the distance. Suddenly he took my hand:

— Would you like us to go there, he said; you will see with your own eyes how strong and pure the Ottomanism is whose truth you cannot believe. Don’t be lazy. Let’s go, let’s congratulate these respectable Ottomans, these loyal peasant Ottomans. Let’s embrace for this great day…

He was pleading more and more. True, the village was only about a thousand meters away. But the stream in between was very steep. To get there would require at least an hour. We would lose an hour and a half from our journey. I didn’t want to. I said we would be late to Razlık. The lieutenant was pleading and insisting, he absolutely wanted to show me the sincerity and loyalty of these poor people. The more I told him to give up, that I accepted his ideas, that I was of one mind with him, that my previous words were nothing but a joke, the more he insisted. Finally I couldn’t resist:

— Alright, let’s go, I said.

He in front, I behind, we descended as if rolling into a deep abyss. The stream was bone dry. The sun had heated the surrounding stones and piles of sandy earth, practically turning it into an oven. Our horses, as if bewildered by this inappropriate journey, would sometimes stop, not wanting to come. At the bottom of the stream we found the road leading up to the village. We would climb up as much as we had descended. Our breath was stopping, we were resting every twenty steps, and climbing again holding onto stones and shrub roots. Pieces of earth were rolling from under our feet, lizards were fleeing, hiding among the hazelnuts. The narrow path became very steep. And we were now taking the hill. One more effort, one more effort… We came out onto a slight plateau. This was in front of the village. Along the edges of newly opened fields, large piles of manure stood. We were only twenty-nine steps from the house with red freedom flags. We stopped. A large dog with weak, yellow fur that suddenly saw us began to bark and jump at us. Pigs of various sizes rooting through the manure with their snouts were looking with their tiny eyes with curiosity as if asking “Who are these?” But a little ahead, at the end of the field, the Bulgarian working with a hoe, as if he hadn’t heard the dog’s barking, wasn’t looking at us at all, wasn’t even curious about who we were.

I looked at the flags hung to celebrate the Tenth of July holiday. These were strings of red peppers hung in the sun to air… A dirty, yellowish brown woman with rolled-up sleeves visible through the low door was surveying us like a wild animal heated up with her treacherous blue eyes, and deliberately not calling the dog that was barking, jumping, going mad around us. The lieutenant, now seeing what the things he thought were freedom flags actually were, was biting his lips, turning pale yellow. In a confused voice, to the Bulgarian in the field:

— May it be easy, gospodin, he said.

The Bulgarian was still not leaving his work, not turning his head to look at us. Again without turning his face, in a harsh accent as ugly as a curse:

— Don’t know Turkish, bre, he shouted.

The lieutenant and I stood frozen. We stood just like that. As if we had been struck. The tableau wasn’t changing. The woman was looking at us with the same treacherous eyes, the dog that became more rabid the more it thrashed around us continued barking, the pigs, as if understanding we were very ordinary and unimportant creatures, imitating their owners, stopped looking at us and began to search for their eternal food in the manure. The Ottoman-Bulgarian citizen working in the field wasn’t turning to look even once, he was occupied with his hoe. I pulled the lieutenant by the arm:

— Come on, let’s go now, I said.

He didn’t answer. Now neither he nor I had the strength or spirit to debate. Like innocent animals left in the desolate abysses of an empty hell, unaware and dazed, we entered the abyss again. We began to slide down the paths we had climbed.

When we reached the top, the goat path leading to the Karaali Inns, I turned around. I looked at the village that remained on the other side of the stream. Indeed, these strings of red peppers that were as bitter as poison were shining from afar very attractively like red freedom flags, giving one the desire to celebrate something no matter what, to shout “Long live! Long live!”